Just started a Tiny Letter, a writing software online in the form of a nifty little newsletter for journalists and writers on the go. Keep in touch with me in real time by subscribing here. Looking forward to hearing from you guys while I send you letters from my account, Dispatches From Brooklyn.

Dubout and Hebdo

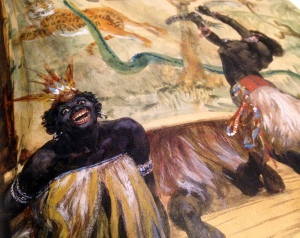

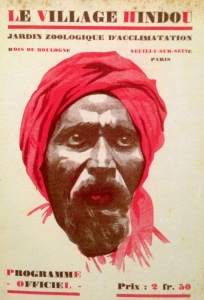

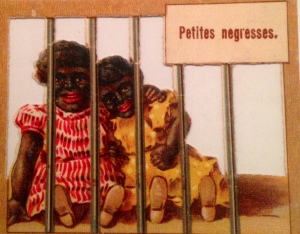

It is 1931 and Le Rire has published a satirical image of a furious-looking ‘savage’ from the L’Exposition Coloniale. The man, scowling at the viewer, is a Black man; a colonial possession from Guinée française. This publication takes place in Paris and the cartoonist is Albert Dubout. Born in Marseille, Dubout is a reputed illustrator and sculptor. His journey into fine art commences with humor, and his artistic endeavors are published in L’écho des étudiants. Like Charlie Hebdo’s publication, he catapults his sense of biting humor at everyone but most particularly, the wrath of his wit – in the era of freak shows and human zoos (and the accompanying horrors of colonial expeditions) held in Chicago, London, Paris, Hamburg, Barcelona, Brussels, Johannesburg and St. Louis – is centered viciously on those who stand helplessly inside the cages instead of the awestruck white viewers outside the bars.

The savage, for Dubout, is the prime target for satire. His mannerisms, complexion, anatomy, displacement but most significantly, his rage is laughable. He is the Other that inspires, partially in fascination and partially in pure contempt for cultural difference and subsequently perceived inferiority, the inspiration for a sense of humor that registers itself as amusing among only those who are not the butt of this joke. His culture, socialization, what he holds precious to his heart – everything – is merely fodder for the next day’s cartoons. If we were to meet him down the road today, Dubout – like his contemporary peers – would insist that the satire had a context, a thoughtful message for civil society to ruminate over, and that his art was not racially-motivated malice at all but “fearless criticism and observation” of an equal “everyone.” Dubout and his modern-day companions forget that “everyone” does not include the Other. A reversal of dynamics: Place the white French body inside the cage and the exotic savage outside; it is no longer satire. Illustrate the white French body as lesser and it is no longer comical. It becomes something else: It is rebellion, and rebellion from the beur, the nègre, the captive is unacceptable. It showcases two inherent contradictions of the claim “everyone can do satire” and “everyone has a right to free speech.” Firstly, it exposes France’s racial hierarchy right away, a deeply embedded component of France’s yesterday and today. Secondly, it unmasks the inconsistency in the liberal claim that free speech is universal and equal. If satire means criticizing menacing institutions and social attitudes, Dubout would create caricatures of white audiences buying tickets for human exhibits or French colonizers in the colonies. If free speech is a human right, L’Exposition Coloniale would never showcase enslaved and silenced human beings to impress around 33 million French citizens in Bois de Vincennes, over six months.

L’Exposition Coloniale would never exist.

–

The Other is incorporated narratively and discursively. It is through speech, art, music, literature, poetry, social gestures, caricatures, and satire – constant discourse – that the Other is simultaneously arranged (against his will) and quartered (again, against his will) by the dominant society’s understanding for its own convenience that is passionately guided by an ill-conceived logic wishing to neutralize the uncivilized threat it assumes the Other poses to them and their civilized values. But the power of such ‘satire’ is unique: As opposed to ‘scientific’ knowledge that Western Europe produced to justify the superiority of its race and the necessity of its imperial expansion, such ‘satire’ added callous amusement to the rationalizing of colonial violence. Through the dominant culture’s created satire, everything that is valuable – culturally and religiously – to the incapacitated Other, is defiled – be it his one God or many Gods or no Gods at all, hymns and canticles, symbols that offer him respite and hope.

Nothing, he is informed, is sacred. But if he dares to apply the same belief of no-sacred-belief to the Master, he is asking for punishment. He forgets that the Master, while claiming nothing is sacred, hypocritically holds many myths sacred to his heart: The myth of European superiority, the myth of White innocence, the myth of irredeemable Blackness and Brownness, the myth of Western provenance of freedom and egalitarianism, and the myth that the Savage represents the sheer “incompatibility” between the West and the rest. The Master, the Other realizes just like himself, is as invested as he is in multiple revered convictions. It just so happens that the Master can guard his and the Other cannot due to a simple equation involving the relentless subtraction of the colonized’s biopolitical power.

That was 1931. Since then, little has changed.

Conventional French intellectual thought still characterizes its immigrants, especially its Muslim immigrants, in colonial patterns; as too ‘different’ and thus backward and inferior to be part of French social fabric. Although human zoos no longer exist in 2014, the cages, cells and dehumanization remain. Muslims in France, predominantly hailing from previously the colonized West and North Africa, make up 12% of the population but constitute 60% to 70% of inmates in the French prison system. Instead of analyzing their financial difficulties as products of France’s failure to integrate its minorities and shield them from racism and exclusion, the delinquency is interpreted as innate to the cultures and religions of immigrants. The onus of integrating into society falls squarely on the excluded, instead of being shared by governing and the governed.

For a country that prides itself on its equality, France has yet to devise a solution for the endemic imbalance in its legal system, particularly its prisons where there are only 100 Muslim clerics for France’s 200 prisons, as opposed to 480 Catholic, 250 Protestant and 50 Jewish chaplains. In addition to this, antithetical to the liberal philosophy of treating social ills with social solutions, France analyzes its Muslim prison problem in sheer political terms. i.e. Islam being the origin of all societal decay. Endemic poverty, racism and perennial stigma are far less important than radical Islam – the purported root of all evil. The extremist is indoctrinated by radical Islam on a Monday and decides to go on a shooting spree on Thursday. French political pathologizing of the issue is merely reductionist, to say the least: It is as if Islam produces itself out of thin air, attacks harmless human beings (harmless and only mourned if they are white and Western) and then neatly folds itself up and vanishes for the time being.

Believe me: I hate comparisons, too. But comparisons allow us to highlight the underlying disjunctions and hypocrisies of dominant societies; that which occurs within and around them; and the (mis)comprehension they are given by the ideologies they put their faith in. Comparisons allow us to move away from black and white analysis of grey and muddied issues. Above all, comparisons provide us much-needed context. Comparisons do not, in this case, mean to excuse heinous loss of life whether that of those killed in the Hebdo shootings or, for that matter lest we forget as most sadly do, the French Muslim woman who miscarried her baby after being repeatedly kicked in the stomach by two French men or those attacked by White skinheads in Lyon, who are out to ‘punish’ those who ‘appear Muslim’ or those fifteen Muslim places of worship attacked after the shootings or the young French Muslim teen who attempted suicide by jumping from the fourth floor of her apartment complex after being assaulted by skinheads for her hijab. Or more.

In addition to carrying the crushing weight of their own dead unacknowledged or (worse) justified by the West, Muslims are demanded to carry the psychological mass and guilt of others’ dead as well by mere association with Islam. And while mourning in solidarity is an endlessly powerful political action that provides immense room for compassion and commitment to better and more stable life and less destruction, this mourning in solidarity never occurs for Muslims. In fact, there is no mourning. The specter of Islam erected in the Western imagination is such that it forces the Muslim Other into a political position of simultaneously being part of a gigantic monolithic community and suddenly no-community at all. It is emotionally taxing but more significantly, it confuses and as we have seen before, confusion – once appropriated – often radicalizes. Context does not excuse what The Kouachi Brothers did. But context provides us the information we need to understand the downward spiral of two siblings. In what appears to be a regular Western thinking pattern – an amnesia of a political kind – the radicalization that the two brothers underwent had little to do with divine Islamic revelation overnight and more to do with the material conditions they found themselves locked within. This includes the Iraq war and torture at Abu Ghraib.

As we bury our dead and instantaneously forgotten in the ground along with those who, too, wanted free speech (take, for example, the 2,332 killed in 2012 alone), we worry if we should apologize for incoming allegation A, B or C. We worry if we should apologize for our dead or not dying fast enough, as the #KillAllMuslims tag suggests. When a shooting occurs or a blast goes off, we nervously scan for skin that resembles ours, accents that inflect as ours do, mannerisms that look un-Western, names that could belong to our sons and fathers, brothers and husbands, friends and colleagues, and we preemptively raise our hands above our heads to provide our status of no complicity. We count our apologies before we can count our own dead. There is no Je Suis Yemen or in more domestic terms, no Je Suis NAACP. There is no Je Suis Muslim for every 30 Muslims killed for one American. We condemn, although it isn’t heard. At least not by the likes of Maher or Murdoch or others. It’s tricky and a little funny in a sad way: Organizing political action against extremism is viewed as suspicious under a State that executes surveillance on Muslim organizations, companies and communities. The paradox isn’t fun to live in. It also isn’t fun to know that when Anders Behring Breivik executed 77 innocent people in the summer of 2011, no anchor on CNN or Fox News, no politician of any party, no hashtag on any social media network demanded that Christians provide collective condemnation and apology to prove they are not fundamentalists. Above all, there was no invocation of Us versus Them. No civilizational discourse that posited Christians as diseased monsters that needed immediate intervention.

The perils of such a totalitarian narrative come the right and the left, the secular and the religious and others: “Today, the dangers of this totalitarian vision can come from many and unexpected sides. It comes from the far-right, which warns us that all Muslims are dangerous and cannot be trusted. It comes from the jihadists, who tell us that Muslims are Muslims and Muslims only, necessarily engaged in a struggle against the rest of the world. The trap here is the binary, the inescapable colonizer/colonized, white/black, collaboration/resistance. In this narrowing of politics, we would either have to be “for” or “against” Charlie Hebdo. In other words, we must vehemently resist seeing this as an antagonism between France and “its Arabs,” or between colonizer and colonized. In the current era of geopolitical tension, from Ottawa to Damascus to Sydney to Algeria, there is no West or East, nowhere to run to, no borders, or barricades that offer protection from terrorism or surveillance.”

But let us return to satire.

All art has context.

There is no such thing as apolitical art. All artistic production – directly and indirectly – is activated by the social and political mobilities and immobilities, deadlocks and solutions, joys and fears of its epoch. And the underbelly roars louder than that above the ground. As we draw what we view evil or plain absurd and mockable in our comprehension, art has the genuis and nimble quality of exposing the cruelties and absurdities wallowing within us as well. The pen speaks for but also of us at both times. Art also demonstrates the hierarchies in our societies based on race, gender, class, geopolitical placement and belonging. Satire – ‘left-leaning’ satire – is supposed to be designed and articulated in such a way that it takes ownership of a taboo idea against bourgeois sensibility and morality. In France’s case, viewing immigrants – particularly Black and Brown immigrants of faiths that the State perpetually distrusts – as human beings who are entitled to the same respect and confidence locals have, is taboo.

Satire would have been mocking the French society and government’s irrational fear of these men and women and children. It would have been taking jabs at the State’s implemented laws to curtail freedom of expression, which – we forget – includes the freedom to wear one’s faith on their body just as it includes organizing public assemblages rallying in favor of a cause for the obliterated, the oppressed. It would have been ridiculing the ages-old xenophobia in French demeanor. It would have been insulting the commonplace and systemic prejudice non-white French citizens and immigrants face on a quotidian basis. It would have been lambasting the colonial attitude that plagues France’s political psyche even today. Satire would have been a demand to unlearn these lethal concepts of Us versus Them. Instead Hebdo in 2014, like Dubout in 1931, lost its opportunity to subvert hegemony – the radical ambition of satire – by aiming the acrimony of its art at the scorned underclasses. It did the opposite of undoing the nonsensical judgments of the powerful: It reinforced the established revulsion for the Other and polarized a society in uglier and more rancorous binaries and dichotomies that do no one well, least of all journalists who become morsels in tragic massacres.

Satire ceases to be satire when it begins to disparage the dispossessed’s sacred. Sacred, in this context, is not because the Gods of these Muslims and Jews amplified their divine potency overnight but because, to the marginalized, faith is all they have in such extreme alienation. Satire is satire when it speaks truth to power and offends those in positions of privilege. But who does satire offend when we ourselves are powerful? Satire becomes something else, something far more sinister when it fails to criticize the disciplinary apparatuses of society and embarks on a witch-hunt for society’s members that already are punished and constantly watched.

The malaise of Charlie Hebdo is not in the extremely racist depictions of Muslims as large-nosed pedophilic Arabs surrounded by flies, perforated by bullets passing through the Quran or Black women as welfare queens or a Black politician as a primate or Jewish people in the most vilifying anti-Semitic tropes or other highly homophobic and sexist depictions of other figures but in Hebdo itself. It is indeed true that Hebdo lampooned everyone and everything (including the Holocaust) in the attitude that nothing is sacred but its focus fell squarely on those living on the bare margins of society. For those situated on the razor sharp ends of a nation that refuses to accept them for their Otherness (a construct enforced upon them against their will) and in a global spectrum and discourse that posits them as criminals par nature, religion becomes exponentially sensitive – and prone to injury, as Saba Mahmood said – because of the incommensurable schism erected between them and secular affect. The malaise is in creating art that waltzes dangerously close to political militaristic notions of Muslims in France.

Don’t get me wrong: Satire should be at the expense of others, always. But it is extremely vital for any aspiring artist to remember the nature of the ‘others’ targeted. If the others include the demonized Other, it is not satire. It is the popular imagination of a paranoid public illustrated on paper. In Hebdo’s instance, the ‘satire’ affirmed the violence the French State deployed on Muslim bodies. Unlike the audience of competent satire that becomes a progressive ally for the underclass, satire of reactionary and fascist nature creates a cannibalistic audience that feeds on the misery of the poor and the pulverized. I draw, too. It would become extremely callous of me, as a Pakistani, to draw caricatures of what is dearest to, say, persecuted and powerless Ahmadis and Christians in Pakistan as an attempt to practice free speech.

With every passing day, it is evident that there is an ill-conceived interpretation – particularly in the West – that understands free speech as the right to hurt everyone. Often, free speech is more about the power-play of identities, privileges and social portability than it is about the religious and the secular. Time and again, we learn that free speech isn’t so free as we would like to think it is. Arthur Asseraf sheds light on the historical context of free speech in France: “France’s iconic law on the freedom of the press passed on 29 July 1881, still enforced today, was designed in part to exclude the Republic’s Muslim subjects.” Just like human rights and the commemoration of the dead become sites of contest and competition for what is mournable and what isn’t, free speech is also a biopolitical luxury allotted to the upper class. To give an example: Take the case of the Black American rapper Brandon Duncan faces life in prison for album lyrics. That’s right. Or in France’s case, less spoken of for reasons we are familiar with, a rapper was jailed for insulting France. Props to no one for guessing the race here.

–

Does this context justify the killings? No.

Is context necessary? Always.

Does this understanding of France’s history trivialize the massacre? No.

Is it possible to condemn killings while critiquing dominant and racist ideologies? Absolutely. I can denounce the shootings without supporting a racist publication’s content. It is, in the very same vein of freedom of expression, my right to do so.

Am I, as a Muslim woman, saddened by these deaths? Yes. Even more so as now I, in my individual capacity, must carry out damage control by telling people – high on media-propelled fear and hatred – that the theological debate on whether we can or cannot draw the Prophet is not as straightforward as you think it is. That, yes, we too have a beautiful tradition of drawing the Prophet in sometimes gentle and sometimes striking colors and situations in miniatures, and that our relationship with such an art goes as far into history as the 1700s. That, yes, we too have contemporary political cartoonists who produce brilliantly shrewd satire in Muslim-majority countries – please explore the works of those in South Asia, Central Asia, Middle East, North and East Africa. Take a look at Sabir Nazar’s work. But all of this is lost on a Western public that continues to seek individual apologies from a 1.6 billion population. Someone has grown so fatigued with this expectation that they have used humor to allay the burden. They came up with an app.

Does this provide a background for white France’s convoluted relationship with free speech and satire? Yes.

Does it tell us that, in an audience, there will be those who will not laugh? Yes.

In the face of good and righteous satire, the powerful does not laugh. The powerful feels threatened by the deployment of wit for the cause of equality and social advancement; the powerful feels cornered. In the face of bigotry masquerading as free speech and satire, the underclass does not laugh. There is no laughter for a simple reason: The relentless subtraction of biopolitical power from the minority allows for little appetite for such reckless humor. One does not laugh simply because such production of images and text reminds him and her of their Otherness, their not-belonging-here-ness, their despised status in a society that refuses – from colonial past to imperial present – to accept them in their beings with their many sacreds. There is no laughter. The Other, like the dominant class, has no wall to feel cornered into. There is no wall because there is no home. In that perilous state-authorized displacement, the Other lives on the edge of society.

And when you inhabit the bare periphery of any nation, it is a little difficult to laugh with the crowd.

–

Recommended readings:

On Debating Dead Moral Questions

Paper Bird: Why I Am Not Charlie

Talal Asad, Saba Mahmood, Wendy Brown and Judith Butler: Is Critique Secular?

The Suspicious Revolution: An Interview with Talal Asad

Ces morts que nous n’allons pas pleurer

Teju Cole on unmournable bodies

No Apology

On my way to class, I take the Q train to Manhattan and sit down next to an old white man who recoils a noticeable bit. I assume it’s because I smell odd to him, which doesn’t make sense because I took a shower in the morning. Maybe I’m sitting too liberally the way men do on public transit with their legs a mile apart, I think to myself. That also doesn’t apply since I have my legs crossed. After a few seconds of inspecting any potential offence caused, I realize that it has nothing to do with an imaginary odor or physical space but with the keffiyeh around my neck that my friend gifted me (the Palestinian scarf – an apparently controversial piece of cloth). It is an increasingly cold October in NYC. Sam Harris may not have told you but we Muslims need our homeostasis at a healthy level. While our bodies regulate our internal fanatic temperatures to remain stable, sometimes it gets a little too chilly so we pull out those diabolical scarves and wrap them around our diabolical necks and diabolically say, “Holy shit. It is cold today, Abdullah.” To which Abdullah replies, “Wallah. My ass is freezing.”

By the time I have figured my criminal-by-default status out, we are on the Manhattan Bridge headed toward Canal Street, which means there is mobile reception. My old white friend is on his iPhone telling his friend something about ISIS. He looks at me every single time he says ISIS or Islamic State. I take it lightly; I don’t want to yell at a guy who looks like his joints would fall out of place if I raised my voice. But it’s insulting and several people look in our direction, at my keffiyeh and at him enunciating ISIS while talking to his friend on the phone. That’s when I debate engagement or flipping him off. I decide on neither but I reach into my bag, which alerts him, and pull out a bomb in the form of a plastic bottle containing tap water.

I drink the water, man. I’m tired.

–

After 9/11, Muslims all over the world but specifically in the West were left suspended in the middle of an imperial dichotomy consisting of the Good Muslim versus the Bad Muslim. The either-this-or-that characterization of Muslim-ness can also be traced to the good ol’ days of Pax Britannica that had its Good Colonized Subjects and then its Bad Colonized Subjects. The GCS was the colonized man or woman who pushed empire apologia and saw the “goodness” and “progression” in being a colonized subject. The BCS was the one who revolted. In contemporary history, the opportunistic binary surfaced in the 1970’s when the United States of America viewed the USSR as the sole threat to its global hegemony and utilized Middle Eastern and South Asian nation states to combat the Red evil. Back then, the mujahideen weren’t menacing bearded men but freedom fighters bravely battling against Soviet incursion in Afghanistan. In a bout of admiration for these righteous warriors, Reagan gifted the local mujahideen hand-held Stinger surface-to-air missiles in a multi-billion dollar program that later on spread out to Iran and as far as Sri Lanka. In 1982, he dedicated the Space Shuttle Columbia to the mujahideen. Once the Soviets retreated, Mother America’s interest in Afghanistan dwindled and funding was terminated. Today the freedom fighters are the Taliban. Lesson: Americans sure know how to show their love.

In the American context, the Good Muslim performed the political role of a liberal apologist and extension of Empire. S/he would celebrate iftar (breaking of fast in Ramzan) at the White House after a speech by the President that highlighted the good that expansionist foreign policy does abroad and increasing surveillance and enforcement of alterity against a minority group back home. These Good Muslims came from a variety of civic, religious, cultural, political and educational institutions that amounts to how well-established but also assimilated they were into the American society. Prefacing every public announcement with the customary “Moderate Muslim” label, the Good Muslim became ultimately a pawn in the ideology and practices of US empire.

The reaction to prove Muslim worthiness in order to garner American approval was understandable: After the attacks, the Islamic community was forced to choose between proving their loyalty to the United States by agreeing with rapidly brutal invasions abroad/domestic civil liberties crisis in the name of security or dissent that would and did elicit social paranoia and legal punishment as well as exclusion. In the name of self-reflection and political correctness as well as empathy for a tragic loss of American life, the American Islamic community forfeited in its own autonomy and demands as citizens to appear less un-American and therefore, less deserving of state-sanctioned retribution.

In this binary, the Bad Muslim is the constant malefactor. Since s/he is fed up with attempting (in distressing futility) to show his/her legitimacy as a human being – forget the title of American as it becomes unavailing in this case – s/he refuses to apologize for Islam. The Bad Muslim is the exhausted Muslim. A Muslim whose morale has been drained by perpetual anxiety, hostility and social marginalization for being seen as a criminal for acts of violence he or she has never committed. The Bad Muslim is the Muslim who makes the mistake of thinking he or she is as human as the next person and should be given a modicum of respect as anyone else would receive, such as the random white American who is never harangued to apologize for what KKK did or modern day Neo Nazis do. The Bad Muslim is unhappy with being profiled “randomly” at the airport, for being rejected employment because his or her name sounds a little too Muslim ergo a little too Al Qaeda or ISIS or Taliban or what-have-you. Unless he or she is rich, a Bad Muslim – who is often a working class individual, a mere wage earner – cannot afford the temporary getaway financial stability provides from this interminable environment of contempt and xenophobia. The Bad Muslim is often aware of RAND-constructed typologies that identify ideological tendencies in Muslim communities and exploit inter-sect divides to promote US strategic interests. Here is a five hundred page report on one of many similar documents. The malice is most evident when the Bad Muslim refuses to cheer on imperial occupations of his or her motherland or provide explanations for on-ground militias that, more often than sadly not, have once received the monetary backing of the same country attacking them. The bitter irony is never lost on the Bad Muslim because the Bad Muslim lives it every single day.

In the eyes of those perpetually seeking an apology from Muslims, I am a Bad Muslim. I don’t put hashtag-suffixed apologies online for what someone else of my faith does. When 9/11 happened, I was as shocked and terrified as anyone else was. We scary-looking Muslims experience human emotions, too. It sounds unbelievable if you’ve been swallowing Fox News and CNN (not much of a difference between both just like Democrats and Republicans operate nearly identical in the eyes of someone living in Pakistan or Somalia or Yemen, ad infinitum) narratives or can’t get enough of Homeland’s racist depiction of Muslims but we Muslims react to unexpected loss of life like any non-Muslim would. We cry, we mourn. We don’t wake up in the morning, like Bill Maher thinks, with the idea that today we will go infidel hunting. Some of us just have a minor existential crisis over what cereal to eat.

It amazes me how topical 9/11 is in the American consciousness when someone asks, “Where were you on 9/11?” I was in front of the television doing my homework. But I often ask: Where were you on 10/7 or 3/20 or 6/18 or 8/6 or 9/6 or 5/15 or the other dates when Western hegemony assaulted the lives of millions of innocent men and women? Where were you when the United States employed white phosphorous in Iraq in 2004 that resulted in a 38-fold increase in leukaemia, female breast cancer, infant mortality, lymphoma and brain tumors; statistics crossing those who survived the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki? More importantly, as an American, when will you apologize?

No amount of polls of Muslims denouncing ISIS will authenticate our humanity to the average Westerner who trusts propagated tropes from a culture industry more than anything else. It does not matter to the average bigot whether 126 senior Islamic scholars hailing from various parts of the Middle East, Europe, South Asia, North Africa and beyond theologically make clear in an open 24-bullet letter that the deeds of ISIS are entirely un-Islamic because to the average bigot, Islam is beyond redemption and its followers deserve to be punished by virtue of the faith they follow. It does not matter if one explains, as Alireza Doostdar does meticulously in this essay, that ISIS is not a religious problem but a political exacerbation that necessitates a contextual understanding of its chronological development and proliferation. This hostility is not innate. One is not born with vengeance for a specific group of people. It is instilled and socialized through social and institutional production of ideology from the State, media outlets, academia and everyday social exchange. It is manufactured by ever escalating dosages of premeditated images, sound bites and seductive rhetoric that lures one into regurgitating falsities about a people. It reaches to a point, as we see today, where simply appearing to be Muslim (as if there is a specific aesthetic embodied by us) elicits some of the most unwarranted suspicion, invasive questions and in many cases, outright violence.

#NotInMyName is a well-intended initiative by Muslims who wish to reassure the world that not all of us are raging extremists who want to see communities burn to ashes. But that’s the problem. In a symptomatic reading of the many sincere apologies coming from young and old Muslims, one should not focus on the overtly stated text but what has not been said in those apologies. What you don’t see is that these messages are coming from harmless men and women who simply want their humanity to be registered in the reactive and hyper-alarmed Western world before they are made to pay for a group that, ironically enough, came into existence as a splinter faction when the United States invaded Iraq. What you also don’t see is that these messages shy away from stating the fact that the biggest victim of ISIS is not the United States or the collective West but the average citizen in Iraq and Syria. Stating this is an offence to American political sensibility, a faculty that endlessly amazes me with its parochial view of the world it inhabits. A haunting image of a masked Muslim man attempting to behead a western journalist injects horror in the Western imagination but if you go back a bit into the past, not many people remember British Royal Marines beheading indigenous communists of Malaya. The methods implemented in taking a human’s life is identical and yet the reactions are polar opposites. In the latter case, majority of the West has little to no memory of such a massacre.

Take it this way: In 2011, white men constituted over 69% of those arrested for urban violence and yet black men made up for the majority of the prison population thanks to the American prison industrial complex. The majority of school shooters and mass murderers in the United States are white men (97% of them being male and 79% being white) from upper-middle class backgrounds. But for some curious reason, Twitter or Facebook or even your favorite news channels have not seen a flood of apologies from white men under the hashtag #NotInMyName. I already expect indignant comments to tell me that these men were lone cases who had mental disorders and no friends because it’s the go-to reason when a white man decides to shoot schools up. Unfortunately, brown and black men cannot use the same excuse. Furthermore, white communities do not worry for their well-being when a white person is indicted with a crime the way non-white communities do. Similarly, when American soldiers go on killing sprees in Afghanistan and other lands under siege, we do not witness social media inundated with American soldiers tweeting #NotInMyName. If anything, we rarely hear of such bloodsport. When Mike Brown was murdered by officer Darren Wilson, we did not see white Americans tweet #NotInMyName to highlight the utter barbarity of Wilson’s racially motivated attack. But we did see over $50,000 donations go to Wilson and the cash came out of white pockets. This list goes on and so does the violence but the apologies never make an appearance. Mass culpability seems to apply to Muslims only in the post-9/11 world.

Let me make it clear to anyone expecting an apology from me: There is none.

I will apologize for ISIS when every single American apologizes for the production of the War on Terror that, like the brilliant Iraqi poet Sinan Antoon says, is the production of more terror and thus, endless war. I will apologize for ISIS when every single white American apologizes for the mass incarceration of black and brown people in the United States. I will apologize for ISIS when I see American men and women post lengthy and introspective apologies for what the US Empire has done to the world, including my native country, since its very advent. I will post an 8,000 word apology when English people email me individual apologies for what the British Empire did to the subcontinent. I will carry a banner around Union Square that reads “I condemn ISIS as a Muslim and everything else you think I’m responsible for because I share an identity with someone else” when I start seeing white Americans wearing shirts that read “I condemn the KKK, slavery, plantations, gentrification, the genocide of Native Americans, the internment camps for East Asians, the multiple coup d’etats my country facilitated abroad, the other 9/11 that Chileans suffered and yet everyone and their mother forgot, Christian fundamentalists who can’t pronounce Mohammad but think all Muslims need to be racially profiled and segregated from the rest of America and a lot more as a white person.” I won’t limit this to whiteness only; I will apologize when every single ethnic, religious group apologizes for whatever someone did simply because, under this debauched logic, they owe the world an apology for sharing an identity. When I start seeing these apologies, I will apologize too.

Until then, no apology.

It isn’t easy. Going back to writing after a two-year quelling block stamps out every fiber of creativity in you. The writer in you will demand that you compose – even paltry little – to keep the stream from drying out but the block is quite literally a sudden wall and that wall has no mercy. So, for two years I didn’t write like I used to and barely found the witty spirit to doodle. It was as if trying to stand up again after being hammered with ennui.

But here I am, again. To those who kept checking this space for updates, I wish to do two things: Thank you and seek your forgiveness. Thank you for being concerned readers and forgive me for my absence, it wasn’t according to my own will – at least most of it. To those who stopped, I completely understand.

So, updates first. I began blogging in my freshmen year without any idea that I would gain popularity from it. Little did I know that I would be named in Guernica’s “top” South Asian bloggers in 2010 or was it 2011? I barely remember. Four years and a few months added on the top and after a resounding Hajj and another dozen equally important experiences socially and politically, I graduated from university in Lahore with a degree in mass communication while working for The Nation in Pakistan as a staff writer. It was an educating stint for me, those months. I applied to graduate school in the field I wanted to pursue in order to enter academia and perhaps one day, write a book. I was accepted on scholarship to my school of choice in New York. I am writing to you all while sitting in a wonderful friend’s spacious apartment overlooking a park and picnic area where underpaid nannies and shrieking children punctuate the audio card of my day. There’s nothing to complain about. I take in everything as I explore the city.

New York is no Lahore. New York City is crowded and anonymous. Lahore is crowded yet everyone knows you. New York has no maternal warmth to it, and that’s fine. Sometimes it’s important to leave the nest and learn to fly on your own. Lahore glows, New York glowers. When I first came here on May 17, I was coming back to the United States after 15-16 years. People usually assume I am undergoing ghastly currents of nostalgia but for now, I am decidedly neutral and calm. Somewhere in the underbelly of my observation, a part of me knows that I am back where I was raised and it is still attempting to understand how to receive – or even reject – this old-new change. I thank New York for giving me the time I need to decode its urban psychology, which is of a myriad of colors. Some dark, some bright, some utterly grey – always visible and coeval in the best and worst ways. Several things I noticed once I moved here: People walk very fast and for someone who already has a brisk and long-striding gait, it is pleasant to walk here (not that the idle sauntering in Lahore was bad). The weather is a lot cooler than Pakistan (and I know the comparison doesn’t fit most perfectly) but when it gets humid, it certainly does drive you crazy – and July isn’t even here yet. Class and class-based racial differences along gaping chasms are most visible here through the window of the subway, and yet politely avoided in discussion if you’re sitting with the wealthy. Sometimes a complete stranger will be kind to you and the trick, as an elderly New Yorker confided to a “bright transplant” like me on the train, is to know where that kindness is coming from. Sometimes kindness has an unkind goal.

It feels strange writing like this; I am more accustomed to addressing you all in satirical tone and silliness and through the stage of doodles and what not. I have been asked if I’ve “changed.” It’s a big question. The answer is cradled in yes and no. I am still the young girl who posted hysterical doodles after consuming raw chocolate powder in her dorm. I am still the same person who doodled ridiculous caricatures of personality types (and ended up making a remarkable lot of passive aggressive enemies – which is fine). I am still the nine-year-old girl who left America and spent well more than a decade in Pakistan, growing up to love it and hate it and love it even more and who, now, is back in the United States. But that isn’t important. What’s important is that you all were generous enough to accompany me in this journey and with now a new chapter opening, I want to thank you for wishing me good luck and for patiently watching me grow.

It isn’t easy returning to writing. It takes courage and consistency to walk through the terrain of your thoughts and gently weave them into a coherent account. But it’s happening finally. And it wouldn’t have been possible without your encouragement.

Thank you for being.

Sincerely,

Mehreen

Of the Neoliberal Feminist

When Lynndie Rana England, along with eleven other American military personnel, was convicted of sexually assaulting and torturing detainees in Abu Gharib, a peculiar stance surfaced in the contemporary discourse of feminism: Among liberal feminists and a certain strata of radical feminists, this comparatively young, white and Western woman was being heralded as righteous harbinger of justice against the specter of the bearded and brown Muslim man. We were told – aggressively and indignantly – that the acceptable strength of womanhood lies in utilizing the liberal state’s apparatus in spreading ‘democracy’ abroad – specifically in the scary Muslim majority East. It was insisted that England was a feminist icon – just like Laura Bush – for hauling Iraqi men around on a leash and assisting the strappado hanging of Manadel al-Jamadi that led to his death. Conveniently omitted from this prototypical account of American justice was the fact that another female American soldier had also recorded the ‘corrective’ rape of an Iraqi teenage boy.

Back home in the United States, Laura Bush was less a feminist and more of a sidekick of her husband. While terming the invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan as a feminist attempt to rescue women from local patriarchal violence, Bush occupied both countries but what he did not mention was how on his very first day in the Oval office, he cut off monetary funding to all international family-planning organizations that offered abortion services to the economically abject and counseling to women suffering domestic abuse. This was nothing new: Former heads of neo-colonial and imperial states have normally hijacked feminist rhetoric for their own nefarious goals. One only needs to throw a cursory glance over the ‘gender egalitarian’ rhetoric of generals from the British Empire that aspired to ‘save’ women from colonies while neglecting the gender violations within their own lands. What did raise eyebrows, however, was the increasingly complicit silence Western feminists displayed while the often-male, often-white heads of states would engage in repressive foreign policy as well as cementing prison industrial complexes in their own countries, which specifically targeted men belonging to the lower socio-economic strata of society.

The theft of feminism is nothing nascent to anyone studying the chronological order of feminist waves but in the past decade – or more now – one cannot help but notice that female liberation has become ensnared in a perilous liaison with neoliberal efforts to construct a free-market society. This is what we call neoliberal feminism; a feminism that finds nothing inherently depraved with the mechanism of neoliberalism. It is not limited to willfully adopting cutthroat capitalist ideals of power that throw families on the fringe of social institutions but it is also, in Foucauldian terms, a ‘conduct of conduct’ that remains pathologically obsessed with individualist achievements attained primarily in the center of neoliberal bureaucracy. The male is, as the author of Saving the Muslim Woman Basuli Deb explained brilliantly, normative in neoliberal feminism and nothing is changed. Under neoliberal feminism, women aspire to corporate ideals of success that – like it or not – largely infringe upon the basic rights of the working class. There is a reason why young women are being purposefully advised by the likes of ex- State Department officials such as Sheryl Sandberg to ‘lean in’ instead of critically questioning the dynamics of elite liberal feminism.

Furthermore, this (quite literally commodified) brand of feminism is produced as the faux discursive modality to portray the West as the bastion of progression and freedom when it is anything but. Let us take into consideration the harrowing fact that the United States is the world’s leader in incarceration with at least 2.2 million people present in the nation’s prisons or jails. Under this neoliberal democracy, a 500% increase over the last forty years has been witnessed as the prison industrial complex grows like a cancer. Absent from the analysis of American liberal feminists fixated on ‘saving women in the Middle East,’ through M16s and missiles is the state-sanctioned precarity that black and brown American women become victims of. You will not hear Laura Bush, or any First Lady of a neoliberal empire, raise this contention and bring international focus – let alone humanitarian intervention – to it. Of course, it gives a bad impression but most importantly, it reveals how hollow the feminist rhetoric of neoliberal feminism is as it only upholds the security of the upper and upper-middle classes while throwing the poor man – and woman – under the roaring bus.

Some would argue that the demise of feminist politics began when Reagan and Thatcher collaborated to promote privatization and deregulation for the sake of safeguarding the freedom of the individual to compete and consume without interference from the state. What many present-day activists for women’s rights forget – or choose to remain blind to – is the mode through which capitalism co-opts all sorts of opposition to its own ends. It’s a slippery and ugly slope. An example of this distressing reality is the emergence of pseudo-emancipating ‘feminists’ who state that pornography – a male-dominated, for-profit exploitative industry built on the flesh of women including underaged girls – is a medium through which women can ‘reclaim’ their sexuality. The irony renders one nauseous but even worse: This liberal understanding of a lone individual’s ‘empowerment’ becomes a tool in the destruction of lives on a macro-social level. Stoya and Sasha Grey, we are told, are the real feminists of modern age while women who refuse to become traumatized objects for male consumers are prudish and ‘anti-liberation.’ Yet again, neoliberal feminism partakes in the physical, sexual, mental and economic abusive profiteering of a woman and her rights.

Material feminism – one that is cognizant of the effect of class on a woman’s life – is vital. A bourgeois variant of feminism serves the bourgeois woman alone, no one else. We have seen the outcome of the imperial feminist and her entrepreneurial sister – both often the same person – and we know what good is the stance to drop bombs on women to save them and the stance that bellows of empowerment meanwhile employing child labor for domestic work. If young feminists of today seek a better tomorrow, they must materialize efforts on collective social justice – instead of individualist advancement – that is exceptionally compassionate to the needs of the overburdened and impaired. It is the only way forward. There is no other way.

Written for The Nation, Pakistan.

Note: On a similar note, it seems as if leftist circles finally see there’s something wrong with Hillary Clinton/militarist feminism. In other news, water is wet.

A Woman of War

As women, when we’re children we’re taught to enter the world with big hearts. Blooming hearts. Hearts bigger than our damn fists. We are taught to forgive – constantly – as opposed to what young boys are taught: Revenge, to get ‘even.’ Our empathy is constantly made appeals to, often demanded for. If we refuse to show kindness, we are reprimanded. We are not good women if we do not crush our bones to make more space for the world, if we do not spread our entire skin over rocks for others to tread on, if we do not kill ourselves in every meaning of the word in the process of making it cozy for everyone else. It is the heat generated by the burning of our bodies with which the world keeps warm. We are taught to sacrifice so much for so little. This is the general principle all over the world.

By the time we are young women, we are tired. Most of us are drained. Some of us enter a lock of silence because of that lethargy. Some of us lash out. When I think of that big, blooming heart we once had, it looks shriveled and worn out now. When I was teaching, I had a young student named Mariam. She was only 11 years old. Some boy pushed her around in class, called her names, broke her spirit for the day. We were sitting under a chestnut tree on a field trip and she asked me if a boy ever hurt me. I told her many did and I destroyed them one by one. I think that’s the first time she ever heard the word ‘destroyed.’ We rarely teach our girls to fight back for the right reasons.

Take up more space as a woman. Take up more time. Take your time. You are taught to hide, censor, move about without messing up decorum for a man’s comfort. Whether it’s said or not, you’re taught balance. Forget that. Displease. Disappoint. Destroy. Be loud, be righteous, be messy. Mess up and it’s fine – you are learning to unlearn. Do not see yourself like glass. Like you could get dirty and clean. You are flesh. You are not constant. You change. Society teaches women to maintain balance and that robs us of our volatility. Our mercurial hearts. Calm and chaos. Love only when needed; preserve otherwise.

Do not be a moth near the light; be the light itself. Do not let a man’s ocean-big ego swallow you up. Know what you want. Ask yourself first. Decide your own pace. Decide your own path. Be cruel when needed. Be gentle only when needed. Collapse and then re-construct. When someone says you are being obscene, say yes I am. When they say you are being wrong, say yes I am. When they say you are being selfish, say yes I am. Why shouldn’t I be? How do you expect a woman to stand on her two feet if you keep striking her at the ankles.

There are multiple lessons we must teach our young girls so that they render themselves their own pillars instead of keeping male approval as the focal point of their lives. It is so important to state your feelings of inconvenience as a woman. We are instructed to tailor ourselves and our discomfort – constantly told that we are ‘whining’ and ‘nagging’ and ‘complaining too much.’ That kind of silence is horribly violent, that kind of insistence upon uniformly nodding in agreement to your own despair, and smiling emptily so no man is ever uncomfortable around us. Male-entitlement dictates a woman’s silence. If we could see the mimetic model of the erasure of a woman’s voice, it would be an incredibly bloody sight.

On a breezy July night, my mother and I were sleeping under the open sky. Before dozing off, I told her that I think there is a special place in heaven where all wounded women bury their broken hearts and their hearts grow into trees that only give fruit to the good and poison to the bad. She smiled and said Ameen. Then she closed her eyes.

Initially written for The Nation anonymously.

Thank you for curating that very brief but important exchange of thoughts between us. The responsibility of a post-colonial nation fighting against imperialism to realize the subtle difference between resisting imperialism and creating our own version of it.

More to show up in this place so stay tuned, folks. It’s always good to interact with you all and I assure you I will be regular very soon. Till then, take care.

Below is a conversation about imperialism, US and Pakistani, and my note about it.

View original post 921 more words

Cookie

Where do I begin?

Ever since I was a little girl, cats weren’t exactly my favorite animals. I didn’t hate them but I didn’t like them either. I loved dogs, gold fish, turtles, but cats – nah. It probably had to do with Pamela’s kitten who scratched me when I was in first grade in Virginia. I was a kid so I didn’t go through the whole mature understanding that hey, cats scratch too if they feel threatened. I thought: All cats are evil four-legged beings who hate me. It was silly, I know.

We came back to Pakistan a while ago. We kept three beautiful dogs – one after the other – and they all lived happy, enriched lives until one got kidnapped and the other two got sick so they had to be put down. I was a kid so the pain of losing a pet was limited to the pain of losing a friend you’d play with every now and then. I cried, sure, but I never felt my heart fall to my stomach with anxiety or fear. I never lost sleep over it. I didn’t grow desperate while walking through narrow corridors of barely attended clinics.

I met Cookie – my Turkish Angora kitten – a few months ago. The very lovely and generous Hanifa Tareen gifted me her from the bunch of adorable kittens Cookie’s mommy, Moto, had. I remember the first time I saw her sitting on the backseat of the car. She was so tiny and afraid. That’s when our bond began; She was like my baby.

The thing with Cookie – and I know every cat owner says that – was that she was exceptionally intelligent and beautiful. My mother, not so fond of felines, fell in instant love with Cookie. My father, a man known for his reserved attitude towards all living beings, morphed into a little boy with Cookie; He couldn’t stop snuggling her, taking care of her needs, making sure I was doing my best job at raising her. My sisters, fond of animals, had the most amusing, fun-filled, warm relationship with Cookie. She became family.

This little tribute is for her.

–

You were so tiny when I met you! Your little pink paws and your little pink nose. And for someone so delicate and tiny in size, you sure had the nerve of a very naughty monkey. You’d hop on book shelves and push my journals down while meowing happily. You’d run around the house with mama’s chador in your mouth. You’d jump from one couch to the other while papa browsed the newspaper. You couldn’t stop pouncing at us for fun. And my oh my, you really did love taking naps with us in bed. Your little paw on my cheek while I snoozed.

Remember the time when you broke my favorite mirror? Or the time you literally tore pages out of my book and hid your face between the pages. Or the time you ruined the curtains. I couldn’t even bring myself to snub you; You looked so innocent while standing in the door. Remember how silly you looked after a bath, huddled up in a warm towel. You taught me so much. From little things like taking responsibility, making sure everything was okay, teaching you manners, learning to build patience to bigger things like preparing myself for losing you, holding you throughout the night, trying not to cry while you breathed your last.

Sometimes when I’d eat a mango slice, you’d snuggle up against me and meow at me. You really liked mango for some reason. Your furry white mouth would be covered with sweet yellow pulp. You used to hide the mango seeds under the bed!

The street below was a sight for you to behold whenever you’d get the chance. Papa would pick you up; hold you in his arms and walk outside, letting you take in the sights and sounds of the city around you. Today when papa was buried you, he was crying. He said he felt a fatherly kind of joy while holding you, showing you the world around you. Remember how adorably clumsy he was with you initially? He didn’t know how to hold you or pet you even but he wanted to show his love so he tried. And you graciously allowed him to. I still remember how you would hop on his knees while he watched TV.

Mama says you left too soon. We tried everything. Three vets and dozens of recommendations but when someone’s time arrives, there’s no stopping it. You had chronic renal failure – your kidneys stopped functioning, your system initiated a quick shut down. It was painful to watch. In the last few hours we spent together, I learned so much from you. I learned that a baby can be a fighter, a warrior in tough times. That a small kitten like you had the spirit of a lioness. That no matter how many times your legs gave in making you collapse to the ground, you did everything in your fragile heart to bring yourself back up. I learned that love should never be measured in the number of weeks, months spent with a cherished one but in the moments that never die, that continue to live forever in our hearts. I learned that lying next to you, my forehead against yours, taught me how to say good bye far better than any other time I’ve said good bye to someone. And I’ve lost human friends to death – not once, not twice but thrice – but I learned that saying good bye to anything, anyone – regardless of what and who they are – can put a little hole in your heart. I learned you took pieces of me, of papa, of mama, of us, with you to heaven.

Before you left us, I held you in my arms and took you to your favorite place in the world: The terrace. Under the full, milky white moon, I strolled to and fro while you blinked weakly at the azure sky. I can’t remember how many times I kissed you and cried against your neck while you breathed slowly. I don’t know if you’ll ever know that I held your paw to my lips and talked to you while you trembled as your system started to shut down. I even tried bribing you back to life. You could have anything you wanted. If only you could have stayed with me a bit longer.

I woke the other two sisters up to let them know you’re about to go. We sat around you, rubbed your cold paws, kissed your forehead, and talked to you. We wanted you to know that we were here, we were trying. And I think you understood. When you started breathing your last, my youngest sister rubbed your belly to keep your warm. We took a clean towel, placed you in it gently, kissed you and closed your eyes. You didn’t wake up.

It was Fajr time – dawn. It was a cool, quiet time. I have never cried for anyone like this before but your sudden departure broke us all. Before the sun would rise, papa took you and buried you near a tree. He wept when he came home. He really loved you. Home is hollow without you.

I lied down. I couldn’t sleep. I half-expected you to pounce at me from somewhere, like you played with me. When the sun was out, its rays reflected on the marble floor and I saw your little paw prints. I cried and tried to remember you in the best moments we shared.

I just wanted to say: Thank you for coming in my life. You taught me a lot but most importantly you taught me to love. Mama, papa, the sisters and I will always, deep down inside, look for you around the corner, playing with your toys. We will sometimes look at your bowl and think you’ll be here for your snack. Sometimes I will cry to sleep and imagine you lying right next to me. You will live forever in our memories.

I love you, Cookie. Enjoy kitty heaven.

Your momma,

Mehreen.

An Open Letter to Maya Khan – P2

Maya Khan,

I have no personal vendetta with you.

Last time I found you chasing morality in parks frequented by lower-middle class citizens (they make fantastic targets for righteous condemnation); this time I found you cheering a minority into a further marginalized, compromised position. A conversion on national TV? In a country where minorities are forced to convert already? “Appalling lack of ethics” doesn’t even cut it.

I refuse to get into the whole “Secularize Pakistan!” vs. “Islamic Republic remains!” debate. I’ll be frank with you: I am sick of my Twitter and Facebook timeline where self-proclaimed “liberal thinkers” compete with self-appointed defenders of religion in a hypocritical race of selective outrage against issues within the country and around the world. Apparently you’re Muslim – and quite a passionate one (albeit misguided, misinformed). So am I. But, again, we’re universes apart. In your mind, it seems from your constant appearances on TV, Islam is not a sacred faith that has, in countless instances in history, guranteed that minority rights need not be sacrificed to consolidate an Islamic republic but a sickening opportunity to cash in on consumer-based ratings. Let us assume that Sunil did indeed desire to convert by consent, which is fine, but to air it on national TV in a country where minority rights remain a shaming case of state negligence and constitutionally-endorsed subjugation is a testimony of your indifference or, sometimes I hope, your unawareness of the ongoing oppression. Indifference is a lot worse than unawareness, Maya. I’m giving you the benefit of doubt here.

A few days ago at the Social Media Summit in Karachi, you were mentioned at the media regulation panel which I was invited to and someone told me how the backlash that took place after your park-chase episode was misogynistic against you because the internet had an easy target: A woman. To an extent, I agree. You and I will never find the same outrage and nasty memes against a lot worse people like, you know, Amir Liaquat Hussain (I think I owe him a letter too, just to say hi). So before I explain my stance briefly, I want you to know that I sincerely mean you no kind of harm at all. I don’t know you personally. I don’t even think you’re a bad person. I just think you really need to evaluate your sense of ethics and content selection. Could you possibly do a morning show on, let’s say, media content and the lack of moral responsibility exhibited by those working in said sector? People would love you for it, Maya – think big ratings. I would thank you for it. What better a topic than discussing the recklessness reporters, talk show hosts and anchors have shown in the past? You could win conscientious hearts with this, you could even bring a change in our media. So rich with talent and content this country, it’s a shame you would choose dating and conversion as themes for your show.

What hurts me the most, Maya, is how you have – like many others – used my faith for consumerism, for shoddy attempts at gaining more ratings and ravings. It hurts me when a friend of mine – a Christian – confides in me that she knows that most of the Muslim population in Pakistan would be extremely outraged had a Muslim been converted on TV in a country where they were a minority. It hurts me when I read how people instantly start defaming Islam, my faith that has inculcated in me a profound respect and harmony for non-Muslims, despite knowing that it was not Islam that taught you to run a talk show on a live conversion but your greed for more hits and your insensitivity to the fact that minorities in Pakistan are already isolated and marginalized, that people of non-state religion already know when to keep their mouths shut, that these people will never know that there are people like me who resent you for you irresponsibility – people who are Muslims – and will never, ever condone such a blatant misuse of faith under the guise of ‘spirituality’ on a cheesy TV show. You hurt and maim what you claim to love – a faith that does not encourage relegating minorities into public objects for viewership. That their conversions are utmost private. That their forced conversions are utmost inhumane. Your idea has again, subsequently, backfired.

I’ll keep it short. I’m not angry at you; I am disappointed and there’s a list I could go through. I am disappointed in the silence surrounding this act of hypocrisy. I am disappointed in those who automatically jumped to accuse Islam of such idiocy, never realizing that it wasn’t Islam but our talk show host here who needed to re-educate herself immediately. I am disappointed in what you done in the name of religion without understanding that such a display is another blow against minorities in Pakistan – whether Sunil did it by choice or not, remains an equally significant issue but you do know how it feels to see someone from your own community leave for another, right? Especially when you’re a minority. The number looks small, the number looks weak, the number looks endangered. It is a clear sign of moral superiority draped in congratulating messages.

Before I end, I want you to know that this is not a message against you. This is a message against the electronic media in Pakistan and those ‘regulating’ it; for allowing such a program to be aired only shows how unfazed this board is by the real and unsettling cases of minority oppression in this country. I don’t want you to be fired – I didn’t in the first place. I don’t even want you to stop your show. I just simply wish you would try to understand the consequences of your words and actions. You have an audience, Maya. You have the power to sway public opinion. If you open your eyes, you could raise the public opinion into making Pakistan a friendlier, peaceful place for all faiths. I wish you would never use religion again and I mean this for every single TV personality out there. Using morality for ratings itself is an immoral act. Exploiting Islam is not a great idea. Like I said before, it backfires.

Some day we’ll meet. Maybe in a park, maybe in a temple, maybe in a masjid, who knows. I hope by then you have set a precedent for horrible TV hosts that media could be used as a tool of change instead of a shallow device for more ratings, less brains. Till then, please don’t give me another reason to write you a letter.

Amir Liaqat Hussain ne hi kaafi tabahi phelayi hui hai.

Sincerely,

Mehreen Kasana

Interview with Murat Palta – Genius Behind Oriental Remakes of Hollywood Classics

“It began two years ago,” according to Murat Palta who studied graphic designing at Dumlupınar University Kütahya, Turkey, “with an experiment to blend traditional ‘oriental’ (Ottoman) motifs and contemporary ‘western’ cinema. After a positive response to “Ottoman Star Wars”, I decided to take the theme further, and developed more film posters using the same technique.”

And it turned out fantastic. Making waves all over the internet and various art e-zines, Palta’s oriental illustrations of Hollywood classics has the perfect aesthetic blend of the east and the west. Dressed up in sheikh garb while taking in the scent of a rose, our chubby villain Darth Vader looks pleasantly carefree among his equally well-dressed minions. Jack from The Shining doesn’t look so threatening either.

Considering how the eastern aspect of his digital illustrations meshed well with my (often critical and harsh) academic pursuits of orientalism and its various forms, I decided to take Mr. Palta’s interview – for some art-education and fun. Our digital doodler was kind enough to take some time out to talk.

Mehreen Kasana: So what’s up these days?

Murat Palta: I’m not studying anymore but I have to finish my internship to get my diploma. I finished graphic department of Dumlupınar University (placed in Kütahya) two months ago [but] there’s an obligatory internship that has to be done. All I am doing [right now] is to deal with it.

MK: How did you get this idea? Is there a precedence to it? Because it seems like the first attempt at blending two eras – and that too with quite some eccentricity.

MP: Me and my brother like to talk about movies. Once we were talking about Star Wars, asking each other “What it would be like if it was [the] Ottoman Empire?” and I illustrated what we had talked [about]. After uploading it to a Turkish website, I recieved nice responses. At the last year of university, I decided to carry it further as my thesis for graduation.

MK: Typical question. How long did it take? All that detail! Especially the Oriental re-creation of Star Wars – I see our iconic villain in quite the relaxing sheikh mode.

MP: I don’t remember much about Star Wars but as far as I remember it took like two days with lots of breaks, of course. On the other hand, the other [illustrations] were totally troubling. In the class, everyone was working on their project but the teacher was also giving some side projects which were unnecessary. So I decided that it was not going to be like this and I stayed at home for two weeks, without going to school. I acted as if it was my job. I used to wake up early, have breaks at certain times. After two weeks, they were finished.

MK: Usually artistic folks don’t enjoy sharing the tricks of their trade. I’ll try this on you: What did you use for your graduation thesis other than your obviously fantastic creativity? Tablet?

MP: Hahah, yes and a computer of course. But seriously, there’s no catch. I just went to the school library, examined the characters and everything about style. Also, I found a book with oriental ornaments. So I digitalized them as patterns. Eveything else was regular: I drew them with a tablet. Of course, there were some characters from the movies that I don’t remember [clearly]. So I paused the scenes where they acted, and drew them on the computer. Before that, I made lots of sketches on paper.

MK: Tough stuff, damn. In one of the illustrations – my favorite, i.e. – Jack is raging while his wife cowers in the bathroom – one of the unforgettable scenes from The Shining. There’s some very nice text in the left and right corners of the drawings – and since I can’t read Turkish (assuming that it is the language) – would you mind translating the particular text above Jack’s head?

MP: Sure. At the right top, it says “lunacy”. This is how the movie is named in Turkey. At the left, above Danny it says: Danny sees twin sisters’ illussion. And above Jack’s head: Jack breaks the door under possession.

MK: Creepy. There are dozens of Hollywood classics. What made you pick the ones in your paintings? Was the selection difficult? Or was it made on a pop culture basis considering how our internet is obsessed with Pulp Fiction jokes and A Clockwork Orange, Godfather references?

MP: We can say all of them were the parts for me to decide. I sought for the movies with three qualities: They had to be titled “classic” or “cult” so that everyone could recognise what the miniatures were about, even though he or she hadn’t seen the movie yet. They had to contain some reflections from western culture. They had to be adapted to eastern culture or miniature style. So these movies had these three qualities – more or less.

MK: It’s hard to believe these are digital illustrations, is what someone exclaimed to me. They further explained how the detail and texture looked amazing thus the disbelief. How long has it taken for you to master strokes and angles on a digital medium? Is it a lot tougher than an actual painting on a canvas?

MP: Sometimes. For instance, personally I like working with paper and pencil. It’s more enjoyable for me and it’s easier. To talk about digital medium, its advantage is colouring. Also, if you make a mistake, it’s easy to take it back. Since I didn’t have much time, I had to make them with a digital medium. Honestly, even if I had time I would still make them [on the same platform]. Because my aim was also to prove that traditional can go together with digital. Controlling strokes and angles didn’t take much time but at first, it was little hard for me to control the tablet. I had been using the mouse [before]. At the time I was working on the project, it had been four months or something since I bought the tablet and till that time, I just used it infrequently. But after all, I made it!

MK: I’ll stop pestering you now. Before I stop, got any tips or friendly advice for aspiring artists and illustrators?

MP: I’m too young to give tips but I can give some friendly advice: I think graphic artists shouldn’t try hard to draw great. Instead, they should try hard to find different ideas so that they can take a [different] step for graphic art.

MK: Thanks for your time, Murat. Awesome work.

Check out the whole set here. There should be a book of these.

In other news: The short film Assad Zulifqar Khan wrote and I co-wrote, depicted in Zia ul Haq’s dark era, is receiving interesting reviews from the audience. Make sure you check out the trailer and the review by Saadia Qamar for Express Tribune.

comments